Chapter 1: Of Notebooks and Flying Machines

The sun is too bright as we scramble outside the Smithsonian Metro station. I lower my baseball cap against the glare. The National Mall—the Nation's Front Yard, as they call it—is jam packed, as always, on a warm weekend. Joggers dot the gravel path, and more than a few Frisbees and footballs fly overhead. Big brown spots reveal where the grass has been trampled by too many visitors over a hot, dry tourist season.

Now that it's after Labor Day, hordes of students and interns from the other side of everywhere join the throng of tourists enjoying these last warm days. Teens pretend not to know the grownups trailing behind them pointing out historical landmarks. Even though Washington is not a majorly polluting city, tour buses do kick up fumes. And me and, my science fair partner Billy Vincenzo are drinking it all in. Oh, and did I mention? We brought my scientist dad along for good measure.

1But allow me to introduce myself. Charley Morton, at your service. Servizio, they'd say in Italian, which I'm trying to learn. I'm just your average thirteen-year-old girl with wild hair, freckles, and braces. (With purple and gray bands. School colors.)

There's too much I need to explore in this world. I love the logic of science, math. The beauty and precision of language. How did that evolve? I want to discover the music of the stars and figure out how to extend human life spans in good health. Through art and anatomy, I'd like to understand the mechanics of the human body as a player moves down the soccer field. Not just to see how a body in motion works, but to improve on speed, economy of motion, and accuracy of the kick. And through forensics, why every human fingerprint is different.

I want to do it all!

And that's why Leonardo da Vinci, the ultimate Renaissance man, is my personal hero. And a big part of why we—Billy, Dad, and I—are visiting the Smithsonian today.

2"Hey, Charley," Billy says, "take a picture for me, would you?" He uses his antique flip phone to point to the Museum of the American Indian looming ahead of us. "The new game I'm building features a virtual world among cliff-dwelling Indians. You know, the Anasazi? I'm gonna make scenes with these prehistoric people living in caves on high cliffs in the Western Plains—scaling the steep canyon walls to get home, hunting, fighting. But seeing the museum design here, in person, I'm like, how could they possibly have carved a village into those rocks?"

"You are such a fossil!" I tease, pulling out my cell phone and waving him to move into the picture. "Why don't you get a smart phone and join the twenty-first century?" But I know that Billy's parents are afraid he'd spend all his time playing games. Or designing them. Which he might.

It's pretty cool, in a nerdy way, because he's smart like me, only way more focused. Billy would definitely qualify as Da Vinci Middle School's geekiest eighth-grader. Some people think I'm the nerd,

3but Billy is more of a gearhead than I'll ever be, because he's got a one-track mind for the tech stuff, whereas I'm determined to study, well, everything. How else to strive to become a modern-day Leonardo da Vinci?

Exploring the National Mall, which stretches from the Lincoln Memorial to the Washington Monument, past the Smithsonian museums, and on to the Capitol building, makes me happy because it's like walking in the footprints of history. I imagine the gravel path running parallel to all the museums as it might have been two hundred years ago: horses and buggies kicking up dust. The Capitol building in cinders after the War of 1812. Men sporting top hats and canes, and corseted women carrying parasols to shade them from the hot sun.

But it was probably nothing like that. What I'd really like is to see these things for myself. If I could, I would interview all the brilliant minds throughout history who, back in the day, radically helped shape the future. In my book, it starts with da Vinci, of course.

4Newton. Copernicus. Darwin. Elizabeth Blackwell, first female doctor in the U.S. Einstein. Marie Curie. And true to this very place in the nation's history, Martin Luther King.

Meanwhile, here I am in cutoffs, tie-dye T-shirt, and sneaks, my wiry hair momentarily tamed into a ponytail under my cap. I've got my iPad—as always—in my backpack and iPhone in my pocket at the ready so I can take pictures for my blog.

This day belongs to my favorite guys—Dad, Billy, and Leonardo. I don't come inside the Beltway often; for one thing, I'm not great in crowds. I can get overwhelmed, and sometimes I get so turned around that I can't figure out which way is up. My parents had me tested after I got lost one too many times on the Metro, and the verdict is I'm "directionally challenged." Not great for someone who dreams of making distant travels—through time, no less.

I hear the beautiful ping of a Snapchat and pull out my phone. Dad gives me that frown.

5"Charley, you know—no texting once we get inside!"

"Duh!" Does Dad think I have no manners at all, I wonder? But I do have to check, because there's the matter of Beth, my once-upon-a-time best friend who has suddenly gone rogue.

Sure enough, Beth's Snapchatted me a selfie looking all Bella Swan—hair died blue-black and freshly straightened, eyes super made up, and waving newly manicured blue nails with little orange dots on them at the camera.

Billy steps in waving his phone with the same Snapchat. "Hey, what's up with Beth—she dressed up for a costume party or something? "

I frown. "Who cares?" I try to throw the question away.

But I do care.

6"Say, you two," Dad, who's been continuing on towards the Air and Space Museum, turns back, seeing we're halted. "Let's not get sidetracked, guys. Something wrong here?"

I stop to think briefly about explaining. But Dad and Billy are both clueless when it comes to the intricacies of teenage girls' minds.

"Never mind." I shrug off Bethy's weird behavior and start down the mall in a sprint, Dad and Billy following in my tracks and straining to keep up.

Dad, panting, stops us right at the foot of the steps to the Air and Space Museum. He really oughta start working out more.

"Hungry, guys?"

I'm always hungry! Looking for food here makes me feel a little like a modern-day urban forager because of all the colors and scents from the food trucks that line the streets around the Mall—

7Lebanese, Thai, Korean, Cajun, and deli, for starters. We all opt for kebabs at the Lebanese truck.

Then, the kid stuff: ice cream, cotton candy, cookies. Rocket Pops are my favorite cool treat, so I'm glad I brought my babysitting money along to indulge (the parents strictly limit my sugar intake, so if I want something special, I have to pay out of my own savings—like a little candy now and then is gonna kill me!). I love sucking the juice out of those red-white-and-blue rockets.

You may think I'm weird, but I collect the sticks, and me and my friends make up fortunes to write on them . . . sort of a fun doodle project. "I'm gonna write one that says, ‘You are going on a long journey,'" I quip, reflecting on my hoped-for plans for somewhere warm during winter break. I stick it in my pocket to add to the collection in my Girl Cave at home.

8In today's heat, I have to chomp down quick on the ice before the sticky stuff drips semi-permanent rivulets of cherry syrup down my arms. I start biting, braces and all, and—brain freeze! I pop off my Washington Nationals baseball cap for a quick thaw.

Billy, orange Push-Up pop momentarily forgotten and dripping onto his shoe, is squatting on his haunches, studying the refrigeration coil system on the ice cream vendor's ancient pushcart.

Dad looks from Billy to me with a quizzical expression [quizzical, isn't that a good word? It means mystified and slightly amused. Sort of like a combo of puzzled and comical] while he munches on his popcorn—one annoying kernel at a time. Between the two of them!

"Can't you hurry, guys?" At this rate it feels like we'll never get to the Leonardo da Vinci Codex exhibit, so I start skipping up the steps to Air and Space.

9Dad has to take big steps to keep up. And Billy . . . well, suffice it to say we keep almost losing him to myriad distractions before we even get inside the doors of the museum!

Once we do make it inside, I hurry past the World War II exhibit and the moon lander. Those I can see anytime. Leonardo's Codex is on display in the same room as the Wright Brothers' first flyer.

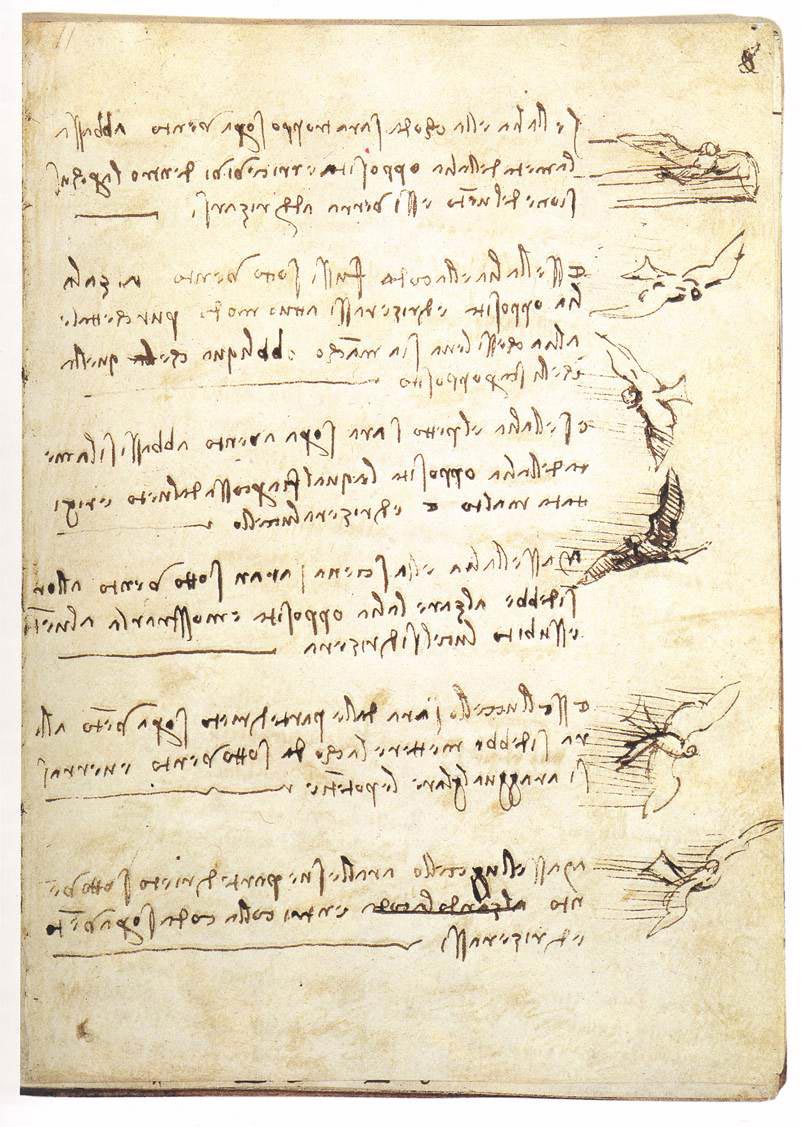

I hear myself babbling in my excitement. "Everyone calls it a notebook, but a codex was a real thing back in the day," I explain to Billy. "Definition: an ancient bound book made up of separate pages. In fact, some of these pages consisting of sketches and descriptions were probably assembled into books after Leonardo's death."

"Um-hmm," Billy murmurs. He's peering up at the wings of an early glider. Not listening.

10"A codex would be like journaling today. Or blogging. You know, like Mrs. Schreiber's asked us to do for the science fair project?"

I check my Instagram—another way a Leonardo da Vinci might record his observations today—and there's a sullen selfie of boy-crazy Beth in her room at home with a stuffed lion in her lap and holding up a piece of paper: GROUNDED. It's all about her sneaking out with chief stud and star Da Vinci Middle School athlete Lex during what was supposed to be a sleepover at my house. So that's that. I think briefly about it—how once upon a time we would've all been science fair partners and she would be here, too. But then I remind myself: that Beth is gone.

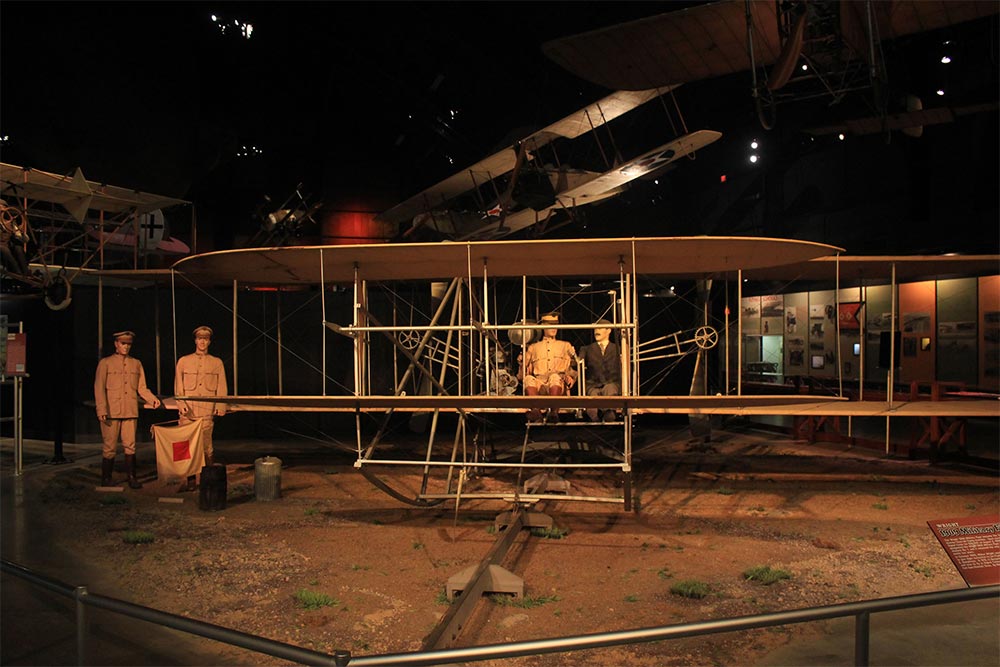

"Hey, Charley," Billy calls, peeling off to get a better look at the Wright Brothers exhibition. "I just want to see this one thing before we get to Leo—the Wright Military Flyer. It's the first military plane ever; it first flew a hundred years ago. Hold up!"

11

"Only a hundred years? That's nothing!" I call behind me.

Billy seems stuck on the Wright Brothers. "What about the science behind manned flight, Charley? You know, for our science fair? After all, Leonardo may have dreamed it, but Orville and Wilbur actually made it happen."

"Yeah. Maybe," I reply without breaking my stride.

"Slow down, Charley," Dad says, tugging on my arm to stop. "Let's not lose Billy."

"Can't wait!" I say, running ahead, for once not caring to keep track of the world's biggest space cadet.

Almost there. Aware there's a crowd, but I don't feel it. I slip between a couple of nuns in their black habits and squeeze past a pod of pale tourists who are staring into their guidebooks, oblivious to the genius before their very eyes.

13

As soon as I find myself in front of the Master's work, I am speechless.

Up front, I take out my phone to start snapping pix. Immediately, an eagle-eyed guard shuts me down: No photos allowed, he says, not even when I explain that I am Leonardo's biggest fan and that the pictures are strictly for educational purposes.

I glance from the Leonardo notebook app on my iPad to the REAL THING; the actual Codex is light years more awesome when I am standing barely an arm's length away from it. And the whole thing is only about the size of a cheap paperback.

But the contents of this ancient paperback are here before my eyes! Sketches and diagrams in the Maestro's own hand! Mirror writing—that was the real da Vinci code—writing from right to left instead of the normal way. Presumably, this was to confuse people who might steal his ideas. But I think it might've been more because he was a lefty and didn't want to smudge the page as he wrote and sketched. I have the same problem.

15And truly, without being able to understand the Italian dialect of the time or being able to hold up the finely written script to a mirror, it would be impossible to decrypt what Master Leonardo wrote and doodled just by looking at it. So the museum curators have been thoughtful enough to translate Leonardo's cryptic handwriting into English as part of the exhibit.

Somebody's poking my shoulder, and here's Billy, panting. "Charley, couldn't you even stop for one minute to see what I'm interested in? I mean, really. Why I even bothered to come down here with you in the first place is beyond me."

"Science fair, Brainiac," I reply, giving him the eye. "Did you forget what we are here for?"

"There's other stuff that's science fair–worthy, Brainiac," he replies. "Weather balloons, for example . . ."

16"Well, if you don't like the idea of recreating one of the experiments of the ultimate Renaissance genius, maybe I'll just find myself another science fair partner. . . ."

"Why are you being so stubborn, Charley?" Billy says, his voice getting louder. "All I'm saying is—"

"I know what you're saying, Billy, and you're missing the point, which is right in front of our noses."

"What point? That Leonardo da Vinci thought he could fly four hundred years before the Wright Brothers did but didn't have the technology?"

"Well, for starters, yes," I say. "If you'd only pay attention. . . ." Suddenly, I notice two of the nuns staring over at us with that schoolteacher stare.

Before I can continue, Dad manages to squeeze his way within earshot. His eyebrows are pulled together angrily.

17"Charley, you see those guards over there? They are ready to eject you from this room. So I suggest you two stop bickering and look quick. There are fifty people behind you now waiting patiently for a close-up view."

"I'm gonna go check out the military plane again anyway," Billy whispers, drifting back toward the Wright Brothers exhibit. "'Cause I think it'd make a cool project for Schreiber's class."

"Hmmph. Once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. And you're about to miss it, Vincenzo," I mutter as he walks away. I take out my iPad to tap in a few notes.

I turn back to the book in the glass case and draw in a breath. Its size makes it hard to study unless you're standing virtually on top of the case. The pages are yellowed and spotted, as you might imagine of something that old.

18And some of it shows the ghost of older writing erased or written over—a palimpsest [this is what they call a manuscript or piece of writing material with the original writing erased to make room for later writing, though traces remain]—because paper and parchment cost so much, and Leonardo was not wealthy, he would've reused the paper. I've read that you can even see his grocery list on some pages. Imagine peering at what was supposed to be notes on flight to find out what he was buying for supper!

Not here, though. These pages show how carefully Leonardo observed the world around him and how meticulously he would capture such things as the array and composition of feathers on the wing of a bird. Or the swirl of currents in the air, that no one could really even see.

"To think he was given the time and freedom to just be curious, to explore, investigate, and follow his passion!" I say wistfully,

19immediately resenting how much of my time is taken up with standardized tests, or memorizing historical facts that anyone could just Google. In fact, I've read Leonardo wasn't even allowed to go to school.

"I wish I'd grown up in Leonardo's time!"

Dad, having heard me on this subject many times before, stops me. "Now, Charley, we've been over this. Italy in Leonardo's day was barely out of the Middle Ages! Leonardo had the ‘freedom,' as you call it, because there was no such thing as public schooling back then. In fact, your Leonardo had to teach himself."

"Wonder how many languages Leonardo knew?" I screw up my eyes trying to decipher Leo's mirror writing for myself.

"Whatever form of Italian was popularly spoken in the fifteenth century," Dad replies. "Ergo, the highly educated would also have to know Greek, Hebrew, Latin—and your Leonardo would have read some of the classics."

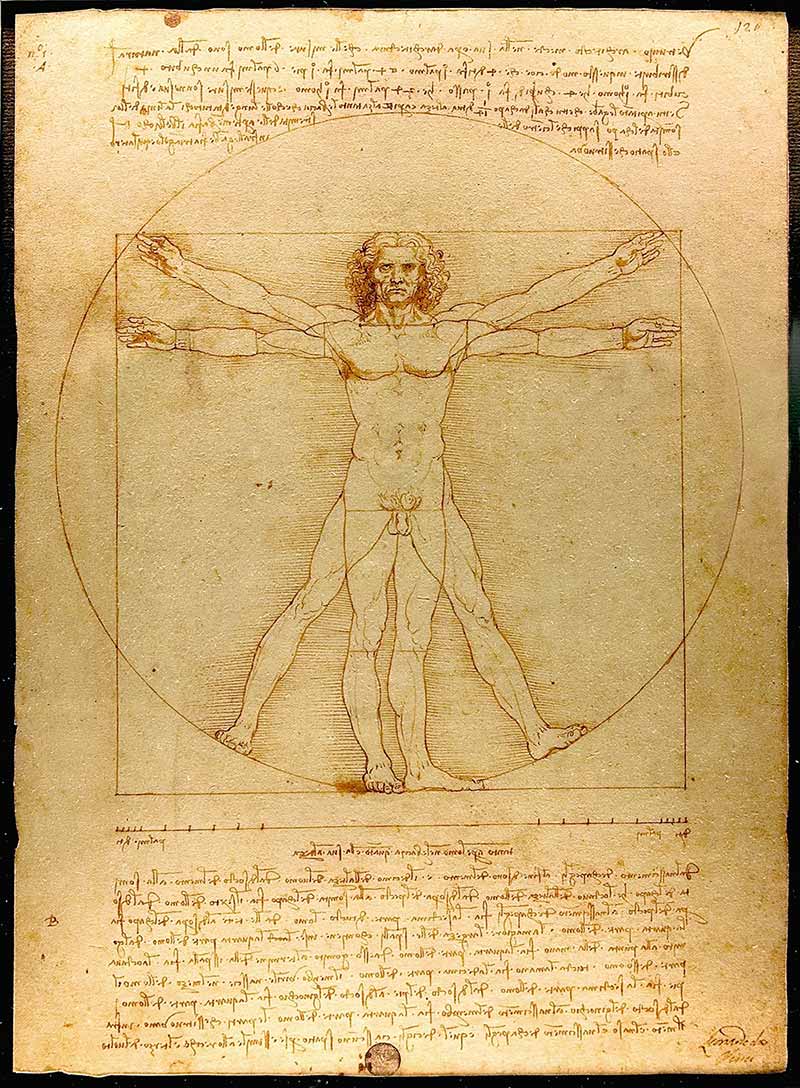

20I consider this as I inspect the drawings of birds and bird wings. This could be the sketchpad of someone whose main preoccupation was drawing, which is the one factoid most people know about the artist who created the Mona Lisa.

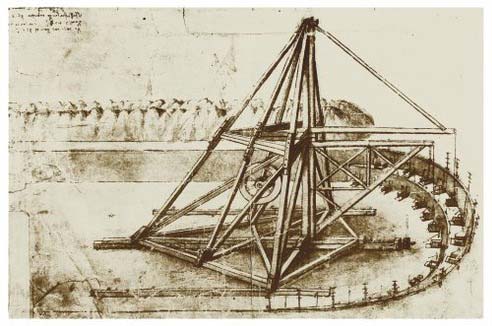

"But Leonardo was clearly a scientist, too. Look at how detailed these drawings are! He even designed a helicopter—look, Billy!"

"Billy?" I turn and bump the arm of an art student sketching her version of Leonardo's sketches, and remember that Billy had already wandered away.

Dad scans the room looking for him. Luckily, Dad is tall and can see over most of the heads in the crowded exhibit. "Don't worry, I'm sure he'll be right back."

"If he doesn't get lost!" I respond, sighing. I turn back to read some of the English translation. As I try to edge in closer another sketch catches my eye—a pyramid-shaped scaffold with a semicircular track around it. "Wow, looks like you'd have to add 'engineer' to his list of accomplishments," I say.

21

"He was indeed a master across many disciplines," Dad affirms.

"The original brainiac!"

Dad chuckles. "In fact, his patrons were often angry at him for starting so many things he couldn't finish. Sound familiar, my little brainchild?"

"Dad, don't you ever wonder how he did it? I mean, surely there weren't enough ten thousand hours in his lifetime to master everything he did!"

Dad just laughs. "Take the long view, Charley. You're only thirteen."

Walking backward to read the signs and notes along the wall, I sigh. "Sure would be nice to interview Leonardo for the science fair."

At that moment, Billy rushes back, excited. "Charley, wish you'd help me think this through. I'm thinking we could build a cool game: ‘When Wars Took Flight.' Whaddaya think?"

23"I think you're totes a gamer geek, is what I think."

I pivot back to study the notebook in the glass case. I try to fix the image of the Codex in my mind like a photograph, though I suspect even photographic memory would fail to capture every line and stroke of genius here. I hope just maybe I can become a little Leonardo-ish by staring at his mirror writing. Then I close my eyes to imagine spying into Leonardo's studio as he captures his world on the page. But there are elbows bumping into me, and I suddenly tune in to all the voices around me. My world, here, today, rushes back. I suddenly feel the crowd closing in on me. Too many people.

"I feel a little faint," I whisper.

Dad puts a protective arm around my shoulder and leads me away from the throng. "C'mon, Charley," he says. "Let's get you out of here."

"Uno momento, pappa," I say. I pull back to soak in Leonardo's Vitruvian Man. Today, it is seen as a symbol of timeless humanity—universal. L'Uomo Universale.

24

I sneak a single photo with my phone and post it to Instagram with the caption: "science fair?" With such a big crowd, no guards seem to notice this time. "Sending to you for later, Billy," I text him. "Could be useful for our project."

Just then, Billy chimes in. He's back. "You know what would be useful, Charley? If you'd take a minute to look at the Wright Brothers before we go."

By the angry note in Billy's voice, I can see it would mean a lot to him. "Sure, Billy. Love to."

But Dad's got his arm around my shoulders, steering me full speed ahead toward the hallway. "Another time, guys. I need to get us home, and Billy to his mom's office."

"Umm, sorry, Billy. Let's come down again when it's not so crowded and spend time looking at what you want to see, 'kay?"

"Yeah, whatever."

26"No, really, I promise we will!"

Billy, not completely convinced, trails reluctantly behind us.

"Imagine being the first to invent a flying machine," I resume, loud enough for Billy to hear. "Leonardo literally dreamed up his flyer almost five hundred years before your Wright Brothers, after making studies of birds' wings. Wonder what he'd make of how far we've come—to the moon, Mars, and now, out of the solar system."

I squirm out from under Dad's arm to walk backward, imagining that long voyage through space and time, even as we observe the history of flight unfolding in the exhibits around and above us. Billy puts his hands out to stop me just before I come crashing into him.

"Guys, do you think time travel is possible?"

27Dad's left eyebrow goes up. "Hmm. I'm not sure I know how to answer that, cara mia."

"I mean, hypothetically speaking?"

This piques Billy's excitement. He's all about the calculus behind the science. "Well, hypothetically, we don't know that it's impossible."

"What if Leonardo actually created plans for a time machine? I mean, flying was only one of his obsessions. But he was, like, inventing the future. Could he have investigated the idea of time travel, you know, to see his future come to pass?"

We're nearing the exit. I can't help taking a skip and almost bump into a stroller coming up from behind. Billy pulls me away just in time.

28"Your da Vinci was definitely a man of science, Charley," Dad says. "But his methods, by today's standards, would be judged as a little loosey-goosey."

That cracks me up. "Loosey-goosey, loosey-goosey!" Outside, I begin waddling and honking like a goose, up and down the stairs outside Air and Space, pretending to tap innocent children on the head as I pass by. "Duck-duck-goose. Squawwk!" I laugh at my own joke, then wait for Dad's eyes to roll. I know I should act my age, but I figure I do enough of that with school and stuff. Sometimes a girl's just gotta let loose—literally!

I spy two guys in Oregon Ducks jerseys passing a football. "Look, Dad. Loosey and Goosey!" I climb over the banister and slide down feet first, reaching the bottom of the steps at the same time as the football flying right at my head.

29"Watch out, Charley—!"

"Ooph!" I hear a sound like air coming out of the fireplace bellows as I hit the ground.

30